Remembering the Ottoman Greeks

Connecting Second Generation Immigrants To Their Roots

By George Topalidis

Edited by Kayla Byrd & Seyeon Hwang

Photo courtesy of George Topalidis

George Topalidis is currently a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law at the University of Florida (UF), and the founder and project coordinator of the Ottoman Greeks of the US Project at the UF Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. He holds degrees from Southern Connecticut State University in History and from the University of Connecticut in Microbiology. His research interests are framed within the field of Historical Sociology and include contested racial identities, U.S. immigration law, and social memory.

I am a first-generation immigrant to the U.S. I was born in Greece to the children of Ottoman Greek refugees.

As a child, I was always told stories about our family’s escape to Greece that impacted the perception of my identity.

My first recollection was when I was five, asking my maternal grandmother to tell me about her life in Northeastern Turkey. I have never forgotten her laconic response, “Leave those things alone my child. They are in the past.” Whatever my grandmother did not tell me, my father and I constantly discussed over dinner and after the nightly news from Greece.

I lived in a home where discussions about religion, politics, and history were welcomed.

My decision to pursue this project came after a seminar led by Dr. Konstantinos Fotiades at the University of Connecticut in 2007 about Cryptochristianity in the Ottoman Empire. At the time, I was working as a research associate in microbiology, a waiter at a local diner, and a part-time instructor at a community college. Inspired by my personal background and passion for the subject, he encouraged me to return to school part-time and study the history of the Ottoman Empire, specifically the immigration of Ottoman Greeks in the United States.

Fortunately, I was able to continue the research at the University of Florida (UF). The Ottoman Greeks of the United States Project (OGUS) at UF is the result of the combined guidance and support of Dr. Paul Ortiz, Director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History program, and Dr. Konstantinos Kapparis, Director of the Center for Greek Studies. Dr. Gonda Van Steen, a former faculty member at UF, and Dr. Alice Freifeld, the former Director of the Center for European Studies, also encouraged me to lead the project.

Established in 2015, the OGUS Project is a multifaceted interdisciplinary research project supported by the UF Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP). Its main goal is to inspire scholarly research about the experiences of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees in the U.S. as well as to raise the public’s awareness of the issues they faced.

To achieve this goal, the project is interviewing descendants of immigrants in the U.S. from regions of the former Ottoman Empire (which constitute contemporary Turkey). Thus far, the OGUS project has collected 251 interviews, and is planned to include more interviews next year.

Who Are Ottoman Greeks?

The Ottoman Greek immigrant cohort consisted of Grecophone and Turkophone Orthodox Christians. The vast majority of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees — like other Southeastern European immigrants — arrived in America between 1900 and 1923.

During this time, major political events motivated their immigration from the Ottoman Empire, while legislation ratified by the U.S. Congress restricted their immigration. Some of those events, specifically the Balkan Wars, World War I, and the Greco-Turkish War, provided the circumstances under which Ottoman Greeks became the target of ethnic violence. This violence has been recognized as genocide by genocide scholars. The OGUS project captures oral histories regarding those events.

Fleeing for Life: Shelia’s Great-Aunt Eugenia

An example of the oral histories collected through the project was documented during an interview with Shelia. Shelia’s great-aunt Eugenia and her family made plans in April of 1922 for her wedding in September of that year, the very month that the city of Smyrna (modern Izmir, Turkey) was burned to the ground by Turkish troops. Sheila recalled the following events surrounding her great-aunt’s wedding.

“My great-uncle, his wife, and his children … they were murdered … I think they were marched off somewhere. She used the word machine-gunned to death. And she was supposed to be married actually the weekend after that happened. They had set for the wedding. But when that happened. They killed the groom. They burned the house that he had built … and along with it all of her proika (dowery). And she barely escaped rape, actually. Only because she ran into the area of town where there were European people, and a French family took her in off the streets. The soldiers were after her.”

Making it to America: Anna’s Family

OGUS also collects information about the journey of Ottoman Greeks to the U.S. Their experiences include time spent in labor battalions in the Ottoman Empire, refugee camps in Greece, and general experiences in Greece and other countries. Their experiences of migration include stories about the journey itself on transport ships, and their arrival to Ellis Island.

Anna, a middle-aged woman from Michigan, recollected the following about her mother’s (Irene) and grandmother’s (Antonia) time as refugees on the island of Mytilene (Lesbos, Greece), the same island that contemporary Syrian refugees are located.

“We slept on the streets. There we suffered starvation, but we had rations. We were given a pot of chickpeas covered in olive oil two fingers thick. The children would eat with their hands and whatever was left we brought back home. We stayed in Mytilene for two years and then moved to Athens where I was put in an orphanage.”

Irene Sklavou (left), Efstratia Hatziathanasiou (middle), and Emanuel Sklavos (right). Photo from Chora, Mytilene, 1927 (Photo Credit: George Topalidis)

The experiences of Ottoman Greek immigrants in the U.S. are the central component of the OGUS project. These include stories about identity, gender roles, discrimination, family, community, organizations, the labor market, culinary arts, music, and languages.

Whiteness & Racialization: Story of Gus

A salient finding of the project is the racialization of Ottoman Greeks by both Greeks from Greece and by American proponents of Whiteness. The former created a racial boundary around Hellenic identity whose essence was, and continues to be, the Greek state-building narrative. The latter created a racial boundary against anyone who was not of Anglo-Saxon stock.

An example of racialization by Greeks from Greece is recounted by “Gus,” a middle-aged male from Ohio.

“There’s one story [that] they were Turkophona. [Meaning,] they could only speak Turkish. So, they came here. They go to the [Greek Orthodox] church, but they’re speaking Turkish. And people [were] saying, ‘What are they doing here? Shouldn’t they be in a mosque?’ Well, they understood what they were saying. That offended some people. Then I heard there was a guy called ‘Big Dan. He was a big man. Whenever there was a problem, people always went to ‘Big Dan’. And they said ‘Big Dan’ went to everybody and called them out and said, ‘We’re going on the other side of town and we’re going to start our own congregation.’”

Artifacts to Remember the Stories

In addition to the oral histories, the OGUS project is working closely with the Digital Collections Library at the University of Florida (UFDC) to curate the over 20,000 images of two and three-dimensional artifacts donated by descendants of Ottoman Greek immigrants and refugees. These artifacts are currently being uploaded onto the OGUS Digital Collection.

One of the artifacts from the collection is donated by Evanthia Gatsinaris, whose ancestors were born on the island of Marmara. As refugees, from the former Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Greeks were forced to evacuate their communities with only items they could carry. A significant number of descendants of those refugees retain gold coins that were brought to the US by their ancestors.

Gold coin with Ottoman script brought from the island of Marmara to Los Angeles (Photo Credit: George Topalidis)

The OGUS UFDC archive also contains images of documents. These documents include immigrants’ autobiographies, correspondence between immigrants and their families in the United States, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire. The documents are written in various languages including: English, Greek, Turkish, Ottoman, and local dialects in the Ottoman Empire.

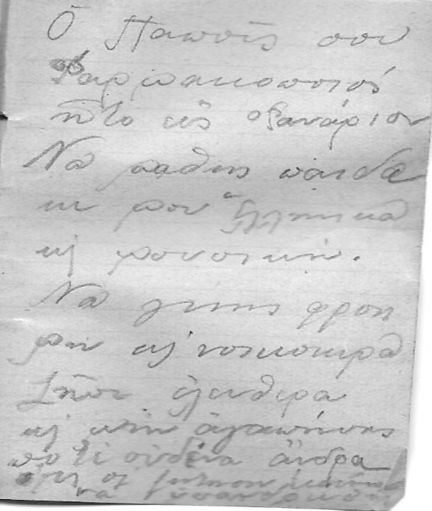

A sample of these documents was donated to the OGUS UFDC archive. It depicts a page from a journal donated by Yvonne Goldman, a descendant of immigrants from northeastern Turkey. It is written by Yvonne’s relative, Roxanne Thomades, in Greek, and lists words of wisdom to her child.

A page from Journal donated by Yvonne Goldman (Photo Credit: George Topalidis)

Three-dimensional images of objects brought from the former Ottoman Empire to the U.S. constitute another category of the archive. An example was donated by Flora Tournidis whose grandparents immigrated from Northeastern Turkey to Canton, Ohio. It is a bronze flask they brought them on their transatlantic journey. Click here to view the three-dimensional model of the flask.

Tracing the Roots

Researchers of the OGUS project are tracing immigration patterns of Ottoman Greek immigrants to the U.S. by collecting data from the Ellis Island Foundation’s online ship manifest archive. This data is being used to construct a GIS map that presents the immigrants’ locations of birth, last residence, ports of departure, ports of call, and final destination.One of the maps created from the data depicts a heat map of the immigrants’ cities of birth in the regions of the Ottoman Empire (constituting contemporary Turkey) and cities of final destination in the United States. Brighter colors on the maps indicate higher populations of immigrants. These maps use a sample of 100 immigrants, however, our researchers have collected over 3,000 immigrant entries and intend to collect more as the process continues.

Heat maps of cities of birth and final destination of Ottoman Greek immigrants (Images by George Topalidis)

In addition, interview respondents have donated maps constructed from the collective knowledge of their local communities. These maps identify the original locations of family homes in urban and rural communities of the Ottoman Empire and provide the opportunity for researchers to reconstruct three-dimensional models of those communities.

A map of Ganochora, Diamond Emery’s Labor of Love (Images by George Topalidis)

Throughout his life Diamond Emery meticulously collected data about the location of the original family homes of immigrants in the towns adjacent to Ganochora. Ganochora and its surrounding towns are located on the European side of Turkey near the coast of the Sea of Marmara. Diamond recently passed away and bequeathed his collection to the OGUS project.

The OGUS project is ongoing. New interviews are being scheduled every six months and images of artifacts are welcomed anytime.

If you have any questions, contact us at ogus0424@gmail.com. Please visit our social-media platform to view our most recent online presentations.

Interested in learning more about the Ottoman Greeks of the US project? Visit our website.

To support the OGUS project visit the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program by click here.

This article is a part of the series for Forward Together sponsored by Islamic Relief USA, Southern Poverty Law Center, Florida Immigrant Coalition, We Are All America, Welcoming Gainesville, ACLU Florida, Reyes Legal PLLC, Mubarak Law, Emgage, Law Office of Karen Winston, CAIR Florida, Human Rights Coalition of Alachua County, Women’s March Jacksonville, University of Florida Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, and Gators for Refugee Medical Relief.

Click on the banner to take the survey for an inclusive and immigrant-friendly future for Florida

Disclaimer: The views, information, or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of WeaveTales and its employees.

Want to tell your story?

For more information contact our editorial admin at contact@weavetales.org.